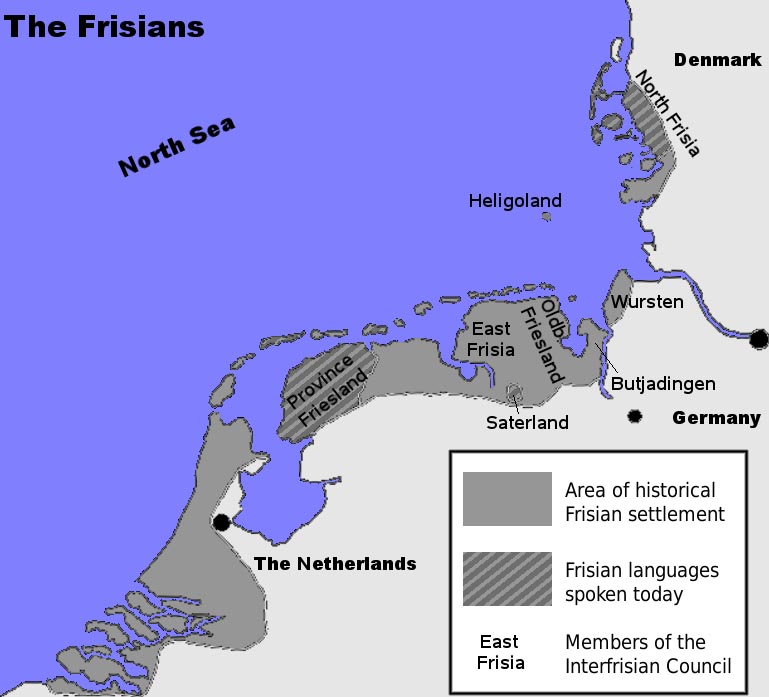

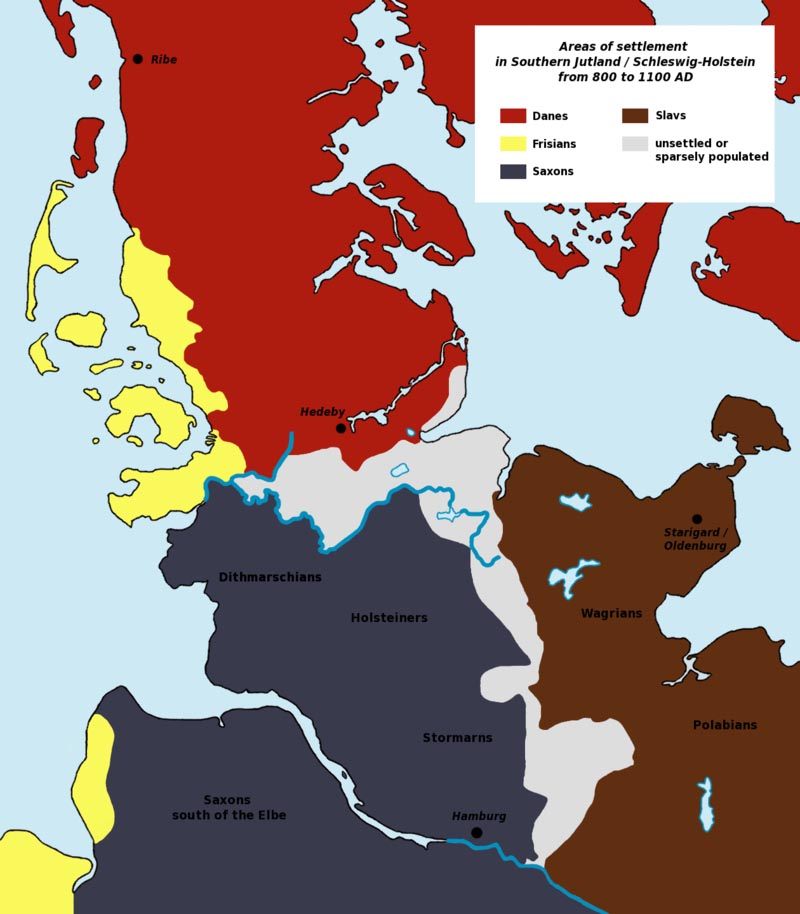

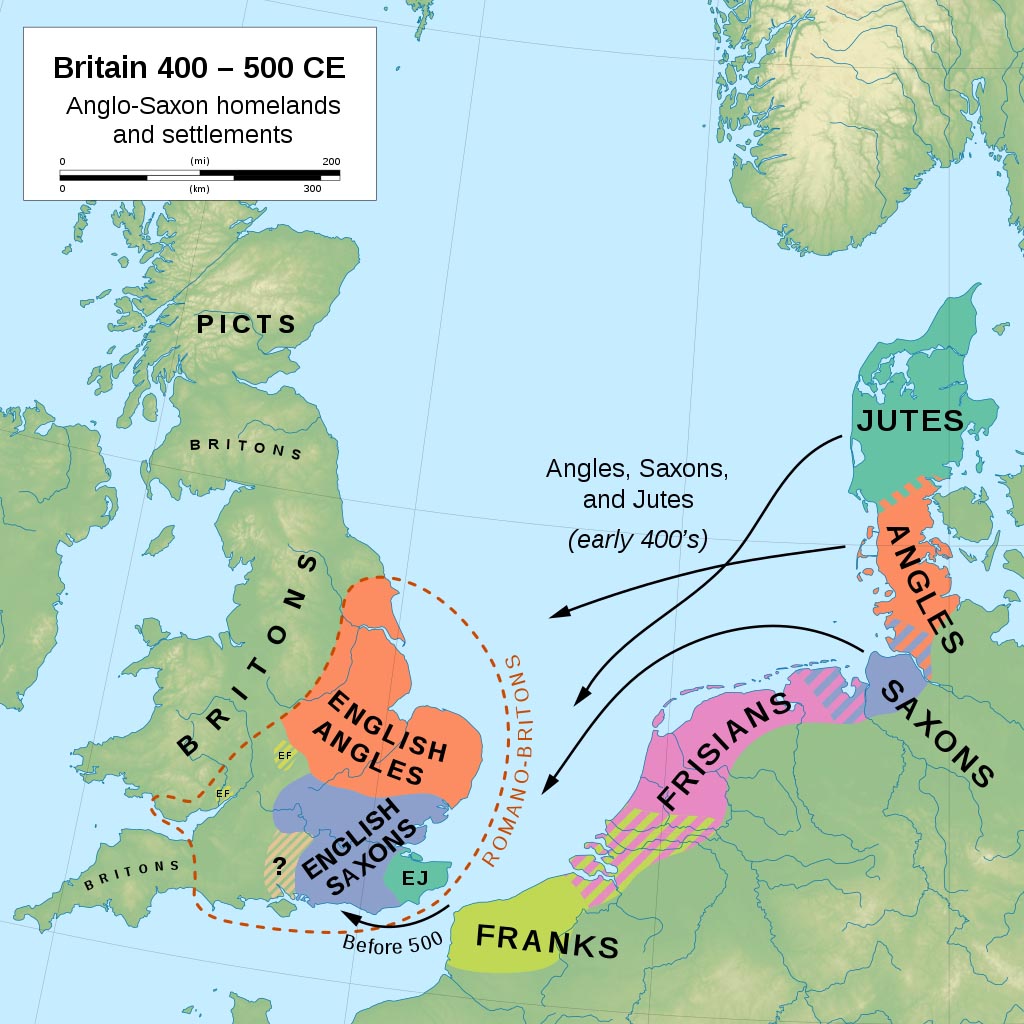

Anglo-Saxon runes has its origins in the older Futhark, but enjoys further in Friesland in the current North-West Germany, where Saxons lived 400 years before they immigrants and occupied the British Isles. “Anglo-Saxon runes” is therefore often called the “Anglo-Frisan runes” in thr litteratue. The language of the Anglo-Saxon inscriptions be both Old Frisian and old-English. The oldest inscriptions can be heathen, but most inscriptions that are found, has Christian content, especially those from the British Isles.

Anglo-Saxon runic inscriptions are found along the coast from today Friesland in North-West Germany to the Netherlands and in England and Skottland.

Anglo-Saxon runes, has been in daily use from 400-500’s to the 900’s, when they gradually went out of brug in line with Viking conquest of England and Skottland, which shows through the many findings of Nordic inscriptions on British Isles from the 900s and later.

The Anglo-Saxon runes, is arguably an successor of the 24-runens older Futhark, when the Anglo-Saxon runic alphabet gradual was expanded with several runes, opposite to what happened in the Nordic countries at the same time. In Scandinavia developed the 24-runers older Futhark to a 16-runers Futhark, while the Anglo-Saxon Fuþorc gradually evolved to consist of 33 runes.

In the Nordic / Germanic runic alphabet is the first 5 runes fuþark, but the first 5 runes in the Anglo-Saxon runic alphabet is fuþorc . Therefore are the the Anglo-Saxon / Anglo-Frisian runic alphabeth primarily called a Fuþorc , after the first 5 runes in the runic alphabet.

The use of runes in England died out around just before the year 1000, and was among others banned by King Knut (1017-1036).

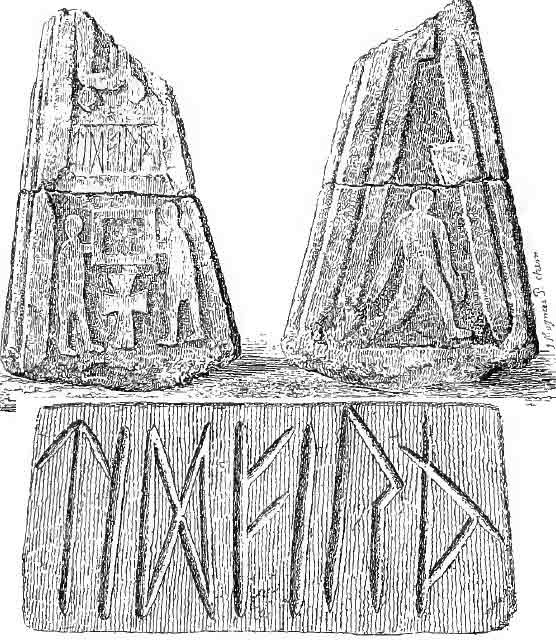

Frisian Runic inscriptions – Runic inscriptions from Friesland

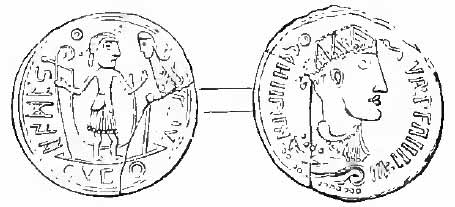

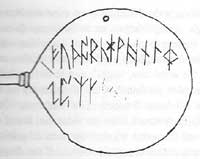

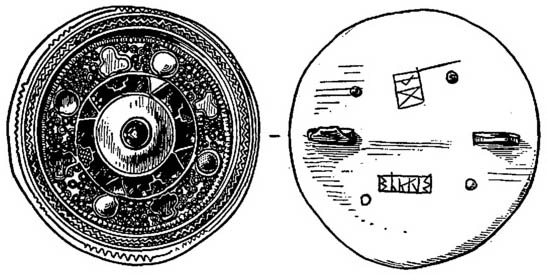

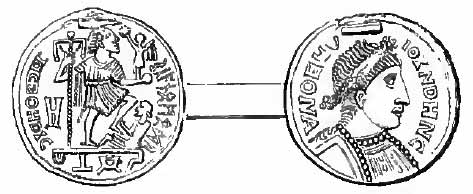

Gold Coin from Harlingen, Frisia. The runic inscription reads hama, ie a man’s name.

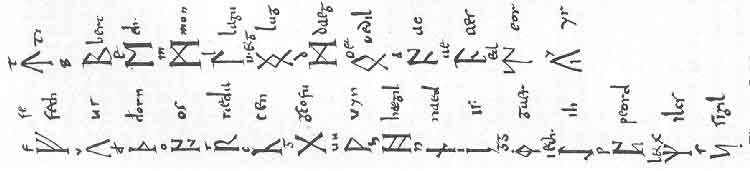

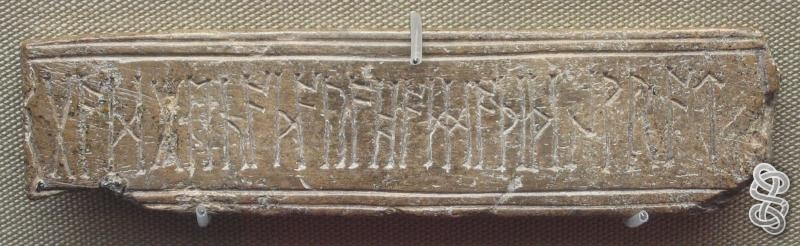

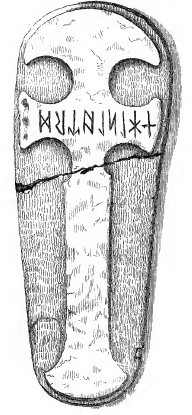

Wooden swore from Arum, Frisia

The Inscription reads:

edæboda

I is a name that shall mean “return-messenger”

Literature:

¤ Ekstern link: The Corpus Of Frisian Runic Inscriptions.

¤ Frisian Runic History.

¤ Runic inscriptions in or from the Netherlands.

The Anglo-Saxon Handwritten Manuscripts

After the Anglo-Saxon runes no longer were handed over in an unbroken tradition, it is from about 900s preserved several handwritten manuscripts, where they anglosakiske runes are described, including in Codex Vindobonensis 795, Salzburg Futhorc (28 runic Futhorc), Hickes’ Thesaurus Anglo-Saxon runic poem (29 runes), Codex Cotton (33 runic Futhorc), Codex Sangallensis 878 (See below).

Salzburg Futhorc (28 Runic Futhorc):

The Runic Poem In Hickes’ Thesaurus:

| 1. Feoh byş frofur fira gehwylcum; sceal ğeah manna gehwylc miclun hyt dælan gif he wile for drihtne domes hleotan. |

2. Ur byş anmod ond oferhyrned,

felafrecne deor, feohteş mid hornum

mære morstapa; şæt is modig wuht.

3. Ğorn byş ğearle scearp; ğegna gehwylcum

anfeng ys yfyl, ungemetum reşe

manna gehwelcum, ğe him mid resteğ.

4. Os byş ordfruma ælere spræce,

wisdomes wraşu ond witena frofur

and eorla gehwam eadnys ond tohiht.

5. Rad byş on recyde rinca gehwylcum

sefte ond swişhwæt, ğamğe sitteş on ufan

meare mægenheardum ofer milpaşas.

6. Cen byş cwicera gehwam, cuş on fyre

blac ond beorhtlic, byrneş oftust

ğær hi æşelingas inne restaş.

7. Gyfu gumena byş gleng and herenys,

wraşu and wyrşscype and wræcna gehwam

ar and ætwist, ğe byş oşra leas.

8. Wenne bruceş, ğe can weana lyt

sares and sorge and him sylfa hæfş

blæd and blysse and eac byrga geniht.

9. Hægl byş hwitust corna; hwyrft hit of heofones lyfte,

wealcaş hit windes scura; weorşeş hit to wætere syğğan.

10. Nyd byş nearu on breostan; weorşeş hi şeah oft nişa bearnum

to helpe and to hæle gehwæşre, gif hi his hlystaş æror.

11. Is byş ofereald, ungemetum slidor,

glisnaş glæshluttur gimmum gelicust,

flor forste geworuht, fæger ansyne.

12. Ger byŞ gumena hiht, ğonne God læteş,

halig heofones cyning, hrusan syllan

beorhte bleda beornum ond ğearfum.

13. Eoh byş utan unsmeşe treow,

heard hrusan fæst, hyrde fyres,

wyrtrumun underwreşyd, wyn on eşle.

14. Peorğ byş symble plega and hlehter

wlancum [on middum], ğar wigan sittaş

on beorsele blişe ætsomne.

15. Eolh-secg eard hæfş oftust on fenne

wexeğ on wature, wundaş grimme,

blode breneğ beorna gehwylcne

ğe him ænigne onfeng gedeş.

16. Sigel semannum symble biş on hihte,

ğonne hi hine feriaş ofer fisces beş,

oş hi brimhengest bringeş to lande.

17. Tir biş tacna sum, healdeğ trywa wel

wiş æşelingas; a biş on færylde

ofer nihta genipu, næfre swiceş.

18. Beorc byş bleda leas, bereş efne swa ğeah

tanas butan tudder, biş on telgum wlitig,

heah on helme hrysted fægere,

geloden leafum, lyfte getenge.

19. Eh byş for eorlum æşelinga wyn,

hors hofum wlanc, ğær him hæleş ymb[e]

welege on wicgum wrixlaş spræce

and biş unstyllum æfre frofur.

20. Man byş on myrgşe his magan leof:

sceal şeah anra gehwylc oğrum swican,

forğum drihten wyle dome sine

şæt earme flæsc eorşan betæcan.

21. Lagu byş leodum langsum geşuht,

gif hi sculun neşan on nacan tealtum

and hi sæyşa swyşe bregaş

and se brimhengest bridles ne gym[eğ].

22. Ing wæs ærest mid East-Denum

gesewen secgun, oş he siğğan est

ofer wæg gewat; wæn æfter ran;

ğus Heardingas ğone hæle nemdun.

23. Eşel byş oferleof æghwylcum men,

gif he mot ğær rihtes and gerysena on

brucan on bolde bleadum oftast.

24. Dæg byş drihtnes sond, deore mannum,

mære metodes leoht, myrgş and tohiht

eadgum and earmum, eallum brice.

25. Ac byş on eorşan elda bearnum

flæsces fodor, fereş gelome

ofer ganotes bæş; garsecg fandaş

hwæşer ac hæbbe æşele treowe.

26. Æsc biş oferheah, eldum dyre

stiş on staşule, stede rihte hylt,

ğeah him feohtan on firas monige.

27. Yr byş æşelinga and eorla gehwæs

wyn and wyrşmynd, byş on wicge fæger,

fæstlic on færelde, fyrdgeatewa sum.

28. Iar byş eafix and ğeah a bruceş

fodres on foldan, hafaş fægerne eard

wætre beworpen, ğær he wynnum leofaş.

29. Ear byş egle eorla gehwylcun,

ğonn[e] fæstlice flæsc onginneş,

hraw colian, hrusan ceosan

blac to gebeddan; bleda gedreosaş,

wynna gewitaş, wera geswicaş.1. Wealth is a comfort to all men;

yet must every man bestow it freely,

if he wish to gain honour in the sight of the Lord.

2. The aurochs is proud and has great horns;

it is a very savage beast and fights with its horns;

a great ranger of the moors, it is a creature of mettle.

3. The thorn is exceedingly sharp,

an evil thing for any knight to touch,

uncommonly severe on all who sit among them.

4. The mouth is the source of all language,

a pillar of wisdom and a comfort to wise men,

a blessing and a joy to every knight.

5. Riding seems easy to every warrior while he is indoors

and very courageous to him who traverses the high-roads

on the back of a stout horse.

6. The torch is known to every living man by its pale, bright flame;

it always burns where princes sit within.

7. Generosity brings credit and honour, which support one’s dignity;

it furnishes help and subsistence

to all broken men who are devoid of aught else.

8. Bliss he enjoys who knows not suffering, sorrow nor anxiety,

and has prosperity and happiness and a good enough house.

9. Hail is the whitest of grain; it is whirled from the vault of heaven

and is tossed about by gusts of wind and then it melts into water.

10. Trouble is oppressive to the heart;

yet often it proves a source of help and salvation

to the children of men, to everyone who heeds it betimes.

11. Ice is very cold and immeasurably slippery;

it glistens as clear as glass and most like to gems;

it is a floor wrought by the frost, fair to look upon.

12. Summer is a joy to men, when God, the holy King of Heaven,

suffers the earth to bring forth shining fruits

for rich and poor alike.

13. The yew is a tree with rough bark,

hard and fast in the earth, supported by its roots,

a guardian of flame and a joy upon an estate.

14. Peorth is a source of recreation and amusement to the great,

where warriors sit blithely together in the banqueting-hall.

15. The Eolh-sedge is mostly to be found in a marsh;

it grows in the water and makes a ghastly wound,

covering with blood every warrior who touches it

16. The sun is ever a joy in the hopes of seafarers

when they journey away over the fishes’ bath,

until the courser of the deep bears them to land.

17. Tiw is a guiding star; well does it keep faith with princes;

it is ever on its course over the mists of night and never fails.

18. The poplar bears no fruit; yet without seed it brings forth suckers,

for it is generated from its leaves.

Splendid are its branches and gloriously adorned

its lofty crown which reaches to the skies.

19. The horse is a joy to princes in the presence of warriors.

A steed in the pride of its hoofs,

when rich men on horseback bandy words about it;

and it is ever a source of comfort to the restless.

20. The joyous man is dear to his kinsmen;

yet every man is doomed to fail his fellow,

since the Lord by his decree will

commit the vile carrion to the earth.

21. The ocean seems interminable to men,

if they venture on the rolling bark

and the waves of the sea terrify them

and the courser of the deep heed not its bridle.

22. Ing was first seen by men among the East-Danes,

till, followed by his chariot,

he departed eastwards over the waves.

So the Heardingas named the hero.

23. An estate is very dear to every man,

if he can enjoy there in his house

whatever is right and proper in constant prosperity.

24. Day, the glorious light of the Creator, is sent by the Lord;

it is beloved of men, a source of hope and happiness to rich and poor,

and of service to all.

25. The oak fattens the flesh of pigs for the children of men.

Often it traverses the gannet’s bath,

and the ocean proves whether the oak keeps faith

in honourable fashion.

26. The ash is exceedingly high and precious to men.

With its sturdy trunk it offers a stubborn resistance,

though attacked by many a man.

27. Yr is a source of joy and honour to every prince and knight;

it looks well on a horse

and is a reliable

equipment for a journey.

28. Iar is a river fish and yet it always feeds on land;

it has a fair abode encompassed by water, where it lives in happiness.

29. The grave is horrible to every knight,

when the corpse quickly begins to cool

and is laid in the bosom of the dark earth.

Prosperity declines, happiness passes away

and covenants are broken.

Litteratur:

¤ Bruce Dickens, Runic and heroic poems of the old Teutonic peoples, 1915.

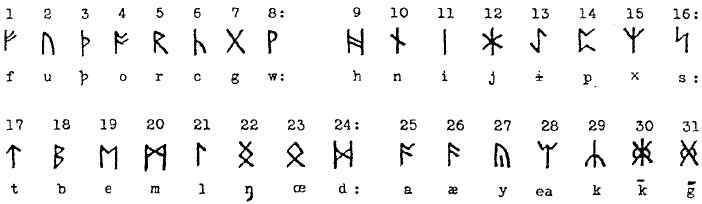

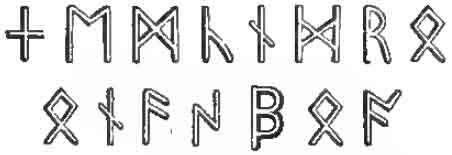

The Anglo-Saxon 31 Runic Futhorc after Dicken’s Transliteration System

Codex Cotton (33 runic Futhorc):

![]()

Hickes’ Thesaurus Grammatica Anglo-Saxonica:

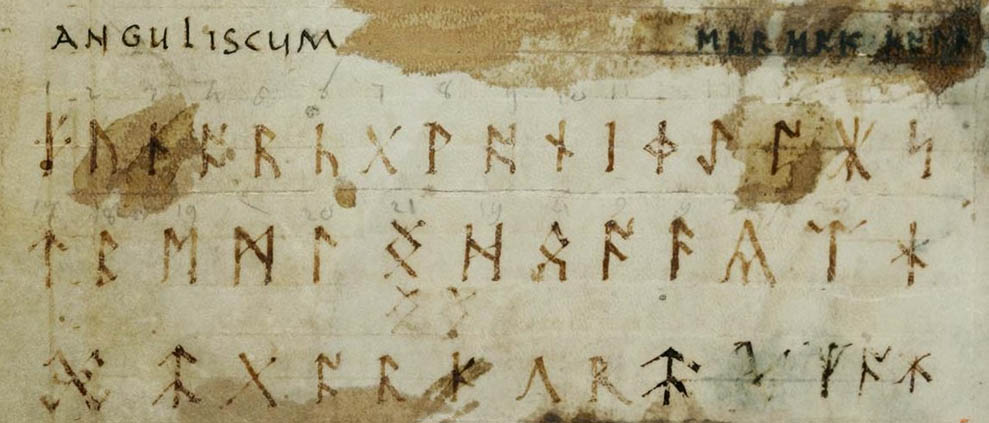

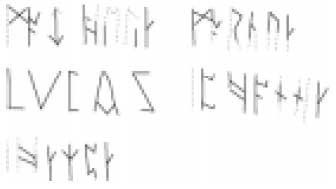

Codex Sangallensis 878:

The Anglo-Saxon futhorc (abecedarium anguliscum) as presented in Codex Sangallensis 878 (9th century).

Literature:

Codex Sangallensis 878.

The Runes Names and Sound Values:

| 1 = Feo …….. f | 12 = Jara …… j | 23 = Daeg …… d |

| 2 = Ur ……… u | 13 = Yr …….. e` | 24 = Otael …… o |

| 3 = Thorn …. th | 14 = Pertra … p | 25 = Ac ………. lang a |

| 4 = Os ……… short a | 15 = Eolh …… r | 26 = Asec ……. short a |

| 5 = Rad ……. r | 16 = Sigel …… s | 27 = Yr ………. y |

| 6 = Ken ……. k | 17 = Tir …….. t | 28 = Ior ………. io |

| 7 = Geofu …. g | 18 = Beroc …. b | 29 = Ear ……… ea |

| 8 = Wynn …. w | 19 = Eoh ……. e | 30 = Cweorp … qu |

| 9 = Hagall …. h | 20 = Mann ….. m | 31 = Calk …….. k |

| 10 = Nied ….. n | 21 = Lagu …… l | 32 = Stan …….. st |

| 11 = Is ……… i | 22 = Ing …….. ng | 33 = Gar ……… hard g |

ANGLO-SAXON RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS

The Brandon pin

Pins is a jewel in many different sizes and shapes, but which in principle is a needle with a head, which is used to attach for example hair or clothing firm. The Brandon needle head has a diameter of 3.6 cm, and it is plated and decorated with two animals with wings. The needle is dated to the late 700s or early 800s.

The runic inscription, which is an unfinished Futhorc, carved into the back of the needle and reads:

fuşorcgwhnijipxstbeml ? doe

There are some scratches after the inscription, which possibly is an attempt to make the Futhorc inscription finished.

Literature:

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1, side 30.

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse, The Making of England, no. 66 b, p. 82.

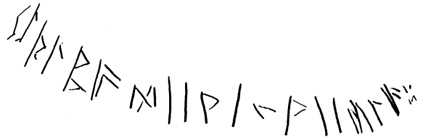

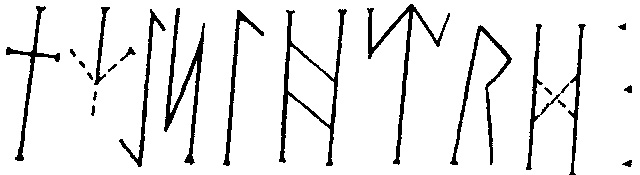

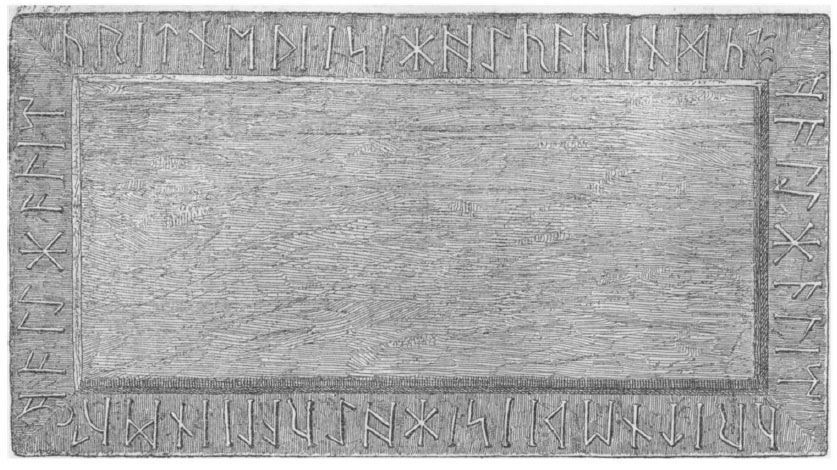

The Thames Scramasax – The Sax of Beagnoth

Navnet….

Navnet….

![]() Futhorc….

Futhorc….

Foto: Wikipedia

Foto: Ogneslav ©

The knife is 81.1 cm long and is dated to the late 800s and was found in the mud in the Thames at Battersea in inner London. Knives of this type were often worn with swords as war equipment, but could also be used as tools, such as when hunting, then it could be suitable for skinning and gutting of animals. The knife also had symbolic significance, and could show your status in society, the full range from a free mand king.

The blade is richly decorated with copper, bronze and silver with zigzag ornaments and it has two runic texts.

The first text reads:

fuşorcgwhnij px.tbe.dlmoeaæyêa

This is a Futhorc, but the order of the runes is unusual and some runes has a distinctive shape as one among others can find in manuscripts. Page believes that the blacksmith who produced the knife, was not wellknown with the runes, but picked up the runic text from a manuscript. This issue is also well know from bracteates.

The secound text reads:

bêagnoş

This is a man’s name, and can either be the name of blacksmith, the owner or the knife.

Litteratur:

¤ The British Museum – Seax of Beagnoth.

¤ Wikipedia – Seax of Beagnoth.

¤ Tumblr.com – Seax of Beagnoth.

¤ Wilson, David M., Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700-1100 in the British Museum, no. 36, p. 146.

¤ Davidson, Hilda R. Ellis, The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England, p. 42.

¤ Gale, David A., ‘The seax’ in Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, p. 80.

¤ Page, R.I., ‘The Inscriptions’, pp. 70-71.

¤ Page, R.I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 113.

The Malton Dress Pin – The Malton Pin

Foto: Ogneslav ©

This needle was found near Malton in North Yorkshire in 1996, and is dated to 700 AD. It is made of bronze, is 7.9 cm long and the head’s diameter is 3.6 cm.

The runic inscription interpreted by Bob Oswald follows:

The first six runes in the inscription is Fehu (F), Uruz (U), Thurisaz (Th), Os (long O), Raido (R), Kaunas (K) and it is the first six runes in the Futhork.

The five runes are Gebo (G), Laguz (L), Ansuz (A), As (diphthong AE, also stated Y in Yorkshire / Durham Dialect) and Ehwaz (E, pronounced UH in the same dialect). You get “GLAYE”.

“Glaye” is a dialect variant of the Anglo-Saxon word Gleaw, meaning quick-witted, wise, sensible or clever.

Literatur:

¤ http://www.christies.com: Bob Oswald

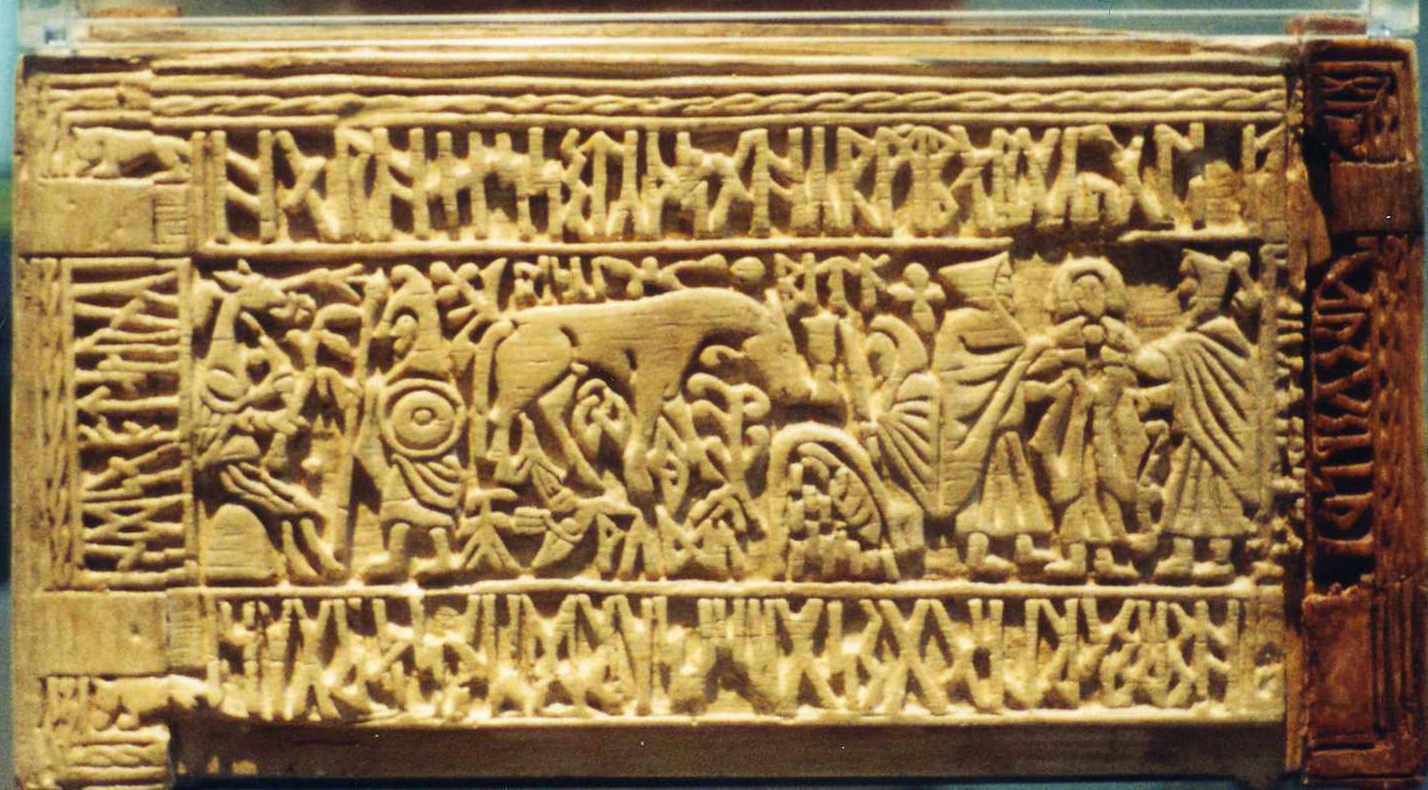

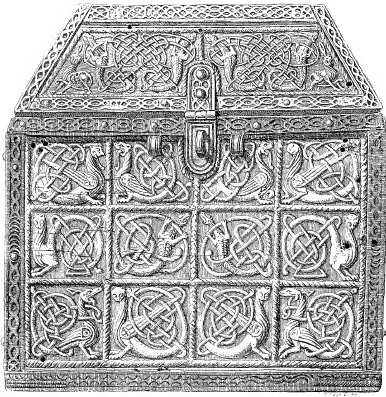

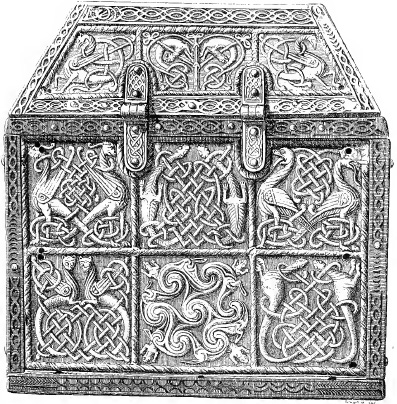

The Franks Casket

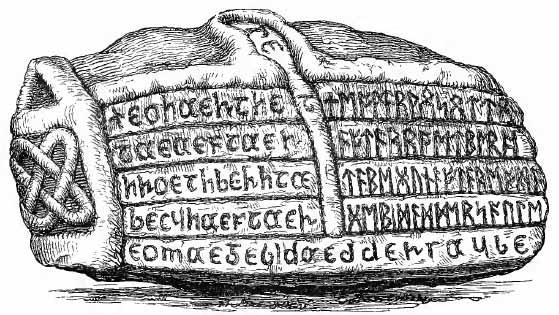

Franks coffin or casket measures 12.9 x 22.9 x 19.1 cm and is dated to ca. 700 AD. It is known that it was in a church in Haute Loire in the 1800s, when it was owned by the Auzon family, and later was split into several parts, but at last all the parts were gathered together and is now in British Museum.

The coffin is a great piece of work, and richly decorated with both Christians and motives related to pagan beliefs. There are eleven inscriptions, beautifully carved on the five sides of the casket. They are all runic texts, with the exception of three words that are skrevt with Latin letters respectively Latin and Old English language.

It is also used secret runes, in that consonants in the inscription are written in plain form, while vowels are replaced with arbitrary shapes.

Photo: flickr.com

Above where the three wise men are depicted, stands a small inscription for himself which reads:

mægi

The text around pictures reads:

fisc · flodu · | ahofonferg | enberig |

warşga: sricgrornşærheongreutgiswom |

hronæsban

Runic text is accompanied to Page, two lines of alliterative verse:

fisc flodu ahof på fergenberig

Warth gasric grorn Thaer han på Greut giswom

According Page can this be translated “the flood lifted up the fish on the cliff-bank. The whale became sad, where he swam on the shingle. Whale´s bone”

The text can be a riddle that describes the origin of the material used to produce the coffin, namely whalebone.

Photo: flickr.com

The left side shows Romulus and Remus being nursed by a wolf (Shewolf) and men with spears at each side on both sides.

The runic text reads:

romwalusandreumwalustwægen | gibroşær |

afoeddæhiæwylifinromæcæstri: | oşlæunneg

The text can be interpreted according Page “Romwalus og Reumwalus, twægen gibroşær, afoeddæ hiæ wylif i Romæcæstri, oşlæ unneg”

“Romulus and Remus, two brothers, a she-wolf nourished them in Rome, far from their native land”.

Photo: flickr.com

The rear panel portrays Titus attack on Jerusalem in the first Jewish-Roman war. In the above section to the left we see the Romans, led by Titus, attacking a domed building, probably the temple in Jerusalem. Top right we see the Jewish population flee. In the lower part to the left where dom is written, announces a sitting judge, the fate of the defeated Jews, who are sold as slaves. In the lower right scene is the one where gisl is written, they are passed away as slaves / hostages.

The inscription is both written with runes and Latin letters, partly in Old English and partly in Latin. Roman letters specified in uppercase.

The inscription reads:

hennes fegtaş titus slutten giuşeasu

HIC FUGIANT HIERUSALIM afitatores

dom / gisl

Here Titus and a Jew fight: Here its inhabitants flee from Jerusalem. Judgement / Hostage

Photo: flickr.com

On the left side we see an animal figure sitting on a small rounded mound opposite an armed warrior with helmet. In mid seen a standing animal, usually interpreted as a horse. At right are three figures with robes with a hood. The two on each side keeps maybe the person in the middle stuck.

There have been very discussion on the interpretation of the runic text, including because runes written without spaces between words, and partly because two runes are broken or missing. It is also used secret runes by vowels is encrypted and written with “unknown symbols”.

Raymond Page reads the inscription:

Hennes Hos sitiş på harmberga

AGL [ . ] drigiş SWA hiræ Ertae gisgraf

sarden Sorga og Sefa torna .

risci / Wudu / bita

Here Hos sits on the sorrow-mound; She suffers distress as Ertae had imposed it upon her, a wretched den (?wood) of sorrows and of torments of mind. Rushes / wood / biter“

Photo: Wikipedia

The inscription reads: aegili

Thats is the mans name Egil

There are many who have argued that the lid of the coffin, because of runetekten aegili portrays a lost legend of a named Egil.

Literature:

¤ The British Museum The Franks Casket.

¤ Wikipedia – The Franks Casket.

¤ J. Huston McCulloch – The Franks Casket.

¤ Wikistrike – The Franks Casket.

¤ Preterist Archive – The Franks Casket.

¤ Asawiki – The Franks Casket.

¤ Video på Youtube – In Focus: Franks Casket.

¤ Bilde av The Franks Casket.

¤ Beckwith, John, Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England, 700-1200, no. 1, p. 18.

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, pp. 86-87.

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England, no. 70, p. 103.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Bruce-Mitford, Rupert, Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archeology. Sutton Hoo and other Discoveries

¤ Alcuin, Alcuini Epistolae, Ernst Ludwig Dümmler (ed.), Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 4, Epistolae Karolini Aevi II, Berolini apud Weidmannos, 1895, letter no. 124, ll. 21-23, p. 183.

¤ ‘Documents bearing on Beowulf’ in Bruce Mitchell and Fred C. Robinson, Beowulf. An Edition with Relevant Shorter Texts, 2006, p. 225.

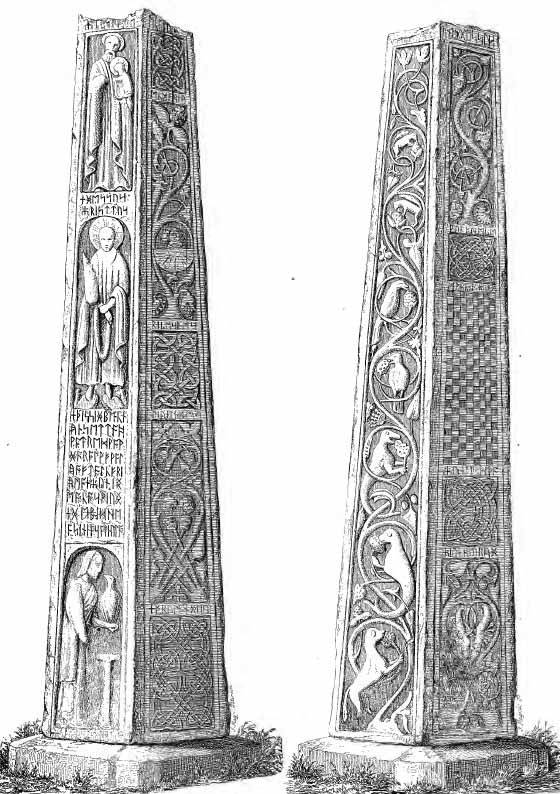

The Ruthwell Cross

Photo:Wikipedia

The Ruthwell Cross is an Anglo-Saxon cross, is probably from 700 AD when Ruthwell was part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria in the current Skottland.

Korset har følgende runeinnskrift:

Krist wæs on rodi. Hweşræ’/ şer fusæ fearran kwomu / æşşilæ til anum.

Christ was on the cross. But then quick ones came from afar, nobles, all together.

The Runic text is a part of “The Dream of Rood”, which is one of the earliest English-language poems. Although the language bears more resemblance to old Scots (the linguistic heritage of Angles in Skottland). The poem contained in a longer version in manuscript form and describes the crucifixion of Christ, set from the cross, and tells the story of his own suffering.

The Dream av Rood:

God almighty stripped himself,

when he wished to climb the cross

bold before all men.

to bow I dared not,

but had to stand firm

I held high the great King,

heaven’s Lord. I dared not bend.

Men mocked us both together.

I was slick with blood

sprung from the man’s side.

Christ was on the cross.

But then quick ones came from afar,

nobles, all together. I beheld it all.

I was hard hit with grief; I bowed to warriors’ hands.

Wounded with spears,

they laid him, limb-weary.

At his body’s head they stood.

There they looked to heaven’s Lord.

Litteratur:

¤ Norsk Wikipedia.

¤ Wikipedia – The Ruthwell Cross.

¤ Youtube video – The Ruthwell Cross and The Dream of the Rood.

¤ Youtube video – The Dream of the Rood – Ruthwell Cross.

¤ BBC – Ruthwell Cross.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

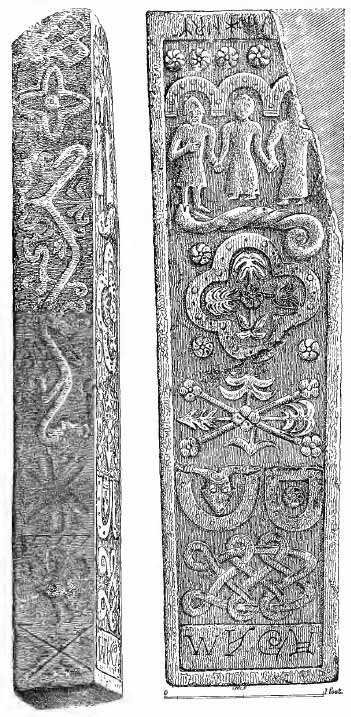

The Bewcastle Cross

Photo: Stephens

The Runic inscriptions on the cross is both worn and damaged over the years, and the interpretation of them are not sure. There are literally that only name Cyneburh is certainly readable on the cross. Cyneburh was a wife of Aldfrith who was king of Northumbria, and died around 664. But Cyneburh was a common name at the time, and certainly can not refer to as Aldfrith wife.

The inscription, which is certainly not interpreted, may sound read: “This slender pillar Hwætred, Wæthgar, and Alwfwold set up in memory of Alefrid, a king and son of Oswy. Pray for them, their sins, their souls”.

The north side contains runes that are not easily readable, but can refer to Wulfere, among others, which was a son of Penda, the king of Mercia, and with reference to Egfrid son Oswy and brother of Alefrid who ascended to the throne in 670, have south side inscription been read as: “In the first year (of the reign) of Egfrid, king of this kingdom [Northumbria]”.

But that said, this interpretation is not sure.

Literature:

¤ Wikipedia – The Bewcastle Cross

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ Wikipedia foto.

¤ www.bewcastle.com foto.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Loveden Hill Urn

Photo: Ogneslav ©

The inscription on a ceramic urn dated 5-6 century AD found in a grave on fire Loved Hill, Lincolnshire. Among the remnants in the urn it was a comb made of bone, fragments of bronze which had been distorted by heat, parts of wooden brooches, pieces of iron and molten glass beads of a chain, showing that it was a dead kvinde of middle rank.

The urn is decorated with deep pressure of a stamp with the same methods like many other Anglo-Saxon urns are decorated. The stamps were often made of bone or wood, and they were used creatively. Pistons designs vary from simple annular stamps with a swastika and stylized snakes. The stamps are sometimes found on pottery in widely different geographic locations, which indicates more of a pottery industry, than one that produces goods for the local community.

The Runes reads:

Photo: R.I. Page

The runes are not interpreted.

Literature:

¤ Wikimedia – Loveden Hill urns.

¤ C. Haith, ‘Pottery in early Anglo-Saxon England’ in Pottery in the making: world-9 (London, The British Museum Press, 1997), pp. 146-51, fig. 1.

¤ J.N.L. Myres, Anglo-Saxon pottery and the se (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1969).

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

¤ J.N.L Myres, A corpus of Anglo-Saxon potter (Cambridge University Press, 1977).

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Thames Silver Mount

Photo: Ogneslav ©

This silver plated handle from 7-8 century is 18.8 cm long and was funded in dredged from Thames, near Westminster Bridge in 1866. It is decorated with an animal head with open mouth, showing teeth and tongue. The eyes are made of blue glass.

The Runic text, which does not make sense, reads:

sbe/rædht bcai | e/rh/ad/æbs

Literature:

¤ Foto fra Wikimedia.

¤ Wilson, David M., Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700-1100 in the British Museum, no. 45, p.153.

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 29.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Page, R. I., ‘The Inscriptions’, p. 78.

¤ Storms, Godfrid, Anglo-Saxon Magic, no. 86, p. 311

The Castor-By-Norwich Astragalus

Caistor-by-Norwich ankle bone is from a deer and found in an urn at Caistor St Edmund, Norfolk, England. The Ankle Bone has an inscription from 500’s with the older 24 runers Futhark and reads:

??? raïhan

roe The inscription is may be the oldest known inscription found in England, and prior to the development of the Anglo-Frisian Futhorc. It has been speculated that the ankle bone may be an import, perhaps derived from Denmark in the earliest phase of the Anglo-Saxon immigration / okupasjon Britania.

The inscription is an important testimony to the Eihwaz-rune and the h-rune with the Nordic simple diogonalkvist, and not the double diogonalkvist, which later became common in the Anglo-Frisian runic inscriptions.

Literature:

¤ Wikimedia – Castor-by-Norwich astragalus

The Chessell Down Scabbard Plate

Photo: Christer Hamp

The Chessell Down sword necklace seizure is made of silver and measures approximately 4 x 1 cm, has a runic inscription, and was found in 1855 in a tomb from about 500 in Chessell Down, near Shalfleet, Isle of Wight.

The inscription reads:

æko : -œri

increase to pain

The runic inscription has also been interpreted as a formula that contains the name Acca. In this case, the text will be the name of the owner, the name of the sword or the name of smith.

Literature:

¤ Christer Hamp – Chessell Down scabbard plate.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

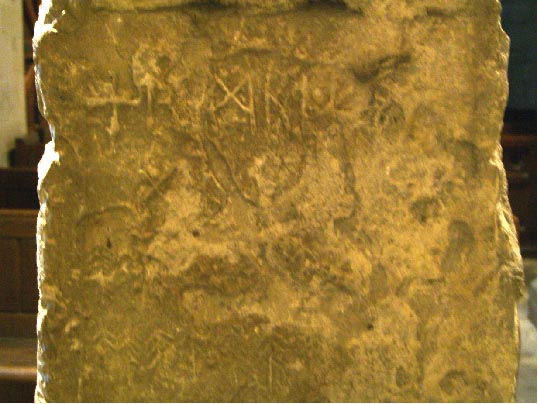

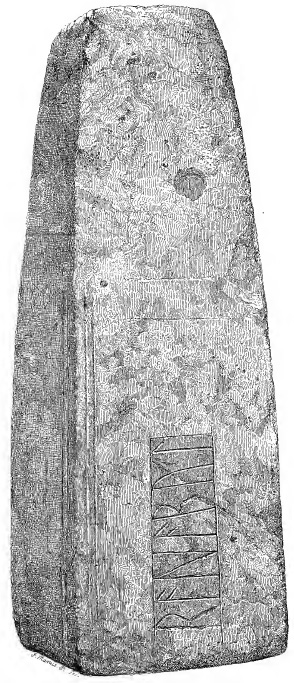

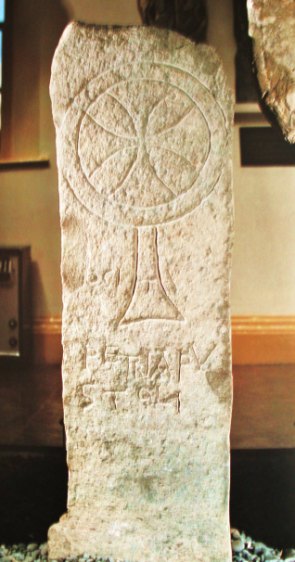

The Crowle Cross

Photo: Stephens

The Crowle cross measures 211 x 40 x 210 cm, and is originally carved out as a cross shaft. It is now located in the rear of the ship in the local parish church of St. Oswald. Until 1919 it was used as a lintel over the west door. Most probably is the stone has been preserved because of the Norman masons reuse, when the church was built in 1150 AD.

The Crowle cross’s age is uncertain, but there is a reasonable degree of certainty that it must have been carved before 1000 AD. The use of runes in England died out around 1000 AD, when it was banned by King Knut (1017-1036) to use runes.

The runes are so worn and broken, that it is difficult to interpret them, but two proposals to interpretation is the following:

Still mind the book, never…”

or

Bestow a prayer upon Nun Lin“.

Literature:

Wikipedia – Crowle cross.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

¤ www.megalithic.co.uk.

¤ Bilde fra wikipedia.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Derby Bone Plate

Photo: Ogneslav ©

It is uncertain how this bone plate is used, but it is dated to the year 700 – 1000. It measures 9 x 2.3 x 0.3 cm and is now preserved in the British Museum.

godgecaşaræhaddaşişiswrat

A good interpretation is not yet found, but Alfred Bammesberger suggest reading the text:

gud GECA şaræ Hadda thi dette Wrat

“God, help this Hadde (a woman’s name), who wrote this”.

Literature:

¤ Bately, Janet and Vera I. Evison, ‘The Derby bone piece’, Medieval Archaeology 5 (1961), p. 302.

¤ Janet Bately and Vera I. Evison, ‘The Derby bone piece’, pp. 302-305.

¤ Bammesberger, Alfred, ‘Three Old English runic inscriptions’ in Old English Runes and Their Continental Background, Alfred Bammesberger (ed.), Anglistische Forschungen, Heft 217 Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg, 1991, p. 134.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

The Dover Brooch

Photo: wikipedia.

The Dover brooch is made of gold and silver, and is dated to the 6th or 7th seventh century. It was found under an excavation of a cemetery in Buckland near Dover, Kent in 1952. The inscription has two runic texts, both with frame lines:

The first contains these three runesiwd.

The second contains 5 runes, where the first is the b and the last is the s or b.

There are not found some satisfactory translation.

Literature:

¤ Vera I. Evison.

¤ Evison, Vera I., ‘The Dover rune brooch’ in ‘Notes’, The Antiquaries Journal, vol. XLIV (1964), pp. 244-245.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Harford Farm Brooch

Photo: R.I. Page

The inscription is written on the back of the brooch, which dated to the 600s.

The inscription reads:

luda: giboetæsi gilæ

“Luda repaired the brooch”.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 103.

¤ Wikipedia – Harford Farm Brooch.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

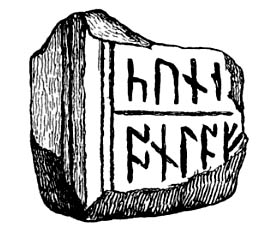

The Dover Stone

Photo: Stephens

The inscription reads:

jislhêard

Gislherd

Gislherd is a mans name.

Literature:

¤ Runes: An Introduction, Ralph Warren Victor Elliott.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Ash Gilton Pommel

Photo: finds.org.uk

The Ash Gilton pommel is a silver plated pyramidal sword pommel dated to the 6th century. It is now at Liverpool City Museum. The inscription is surrounded by ornamentation and is not so easy to read. A pommel is part of the handle of a sword.

The inscription reads:

????![]() ?????

?????

?? emsigimer ????

“? I am … victory ??????”.

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Gilton Pommel

The silver gilt sword pommel from Gilton, Kent, is now in Liverpool Museum. The inscription is read as a x-rune, which is rare rune in the Anglo-Saxon England, since it represents a sound that is not required in old English. Just a few examples of rune is handed over. In manuscripts the x-rune is called “eolhx, iolx or ilx,” a name that is associated with the old English verb ealgian, which means “to protect”.

A pommel is part of the handle of a sword.

Literature:

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

The Faversham Pommel

Photo: finds.org.uk

The silver plated sword pommel from Faversham, Kent, is now preserved in Britsh Museum. At each end of the pommel, there is a t-rune. Since this rune is written on a sword, it can fit to interpret rune as a ideograph. The Anglo-Saxon name for t-rune is “tir / resort”, referring to Tiw, the Germanic god of war.

A pommel is part of the handle of a sword.

This is perhaps an example of what we read in verse 6 in Sigerdifamal:

| Sigrúnar skaltu kunna, ef şú vilt sigr hafa, ok rista á hjalti hjörs, sumar á véttrinum, sumar á valböstum, ok nefna tysvar Tı. |

Seiersruner skal du riste om du vil seier ha skjær dem på sverdets hjalt somme på vettrimer somme på valboster nevn så to ganger Ty |

Victory Runes should you know If you want to have victory carve them on the sword’s hilt some on the sheath some on the blade name then Tiwaz two times |

Since this inscription also is from Kent, as the Holborough spearhead, it can also be a possibility that this is a could be a kind of a signature (Evison).

Literature:

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

The Holborough Spearhead

This iron spear from the 7th century is showing an another example of an possible inscription of the t-rune (0.5 cm), ![]() , in this case, it is sandwiched contrast in the metal.

, in this case, it is sandwiched contrast in the metal.

Since this rune is written on a sword, it can fit to interpret rune as a ideograph. The Anglo-Saxon name for t-rune is “tir / resort”, referring to Tiw, the Germanic god of war.

A pommel is part of the handle of a sword.

This is perhaps an example of what we read in verse 6 in Sigerdifamal:

| Sigrúnar skaltu kunna, ef şú vilt sigr hafa, ok rista á hjalti hjörs, sumar á véttrinum, sumar á valböstum, ok nefna tysvar Tı. |

Seiersruner skal du riste om du vil seier ha skjær dem på sverdets hjalt somme på vettrimer somme på valboster nevn så to ganger Ty |

Victory Runes should you know If you want to have victory carve them on the sword’s hilt some on the sheath some on the blade name then Tiwaz two times |

It resembles the tradition of the Faversham pommel, which also has t-rune. Since this inscription also is from Kent, as the Holborough spearhead, it can also be a possibility that this is a could be a kind of a signature (Evison).

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 92.

¤ www.kentarchaeology.org.uk.

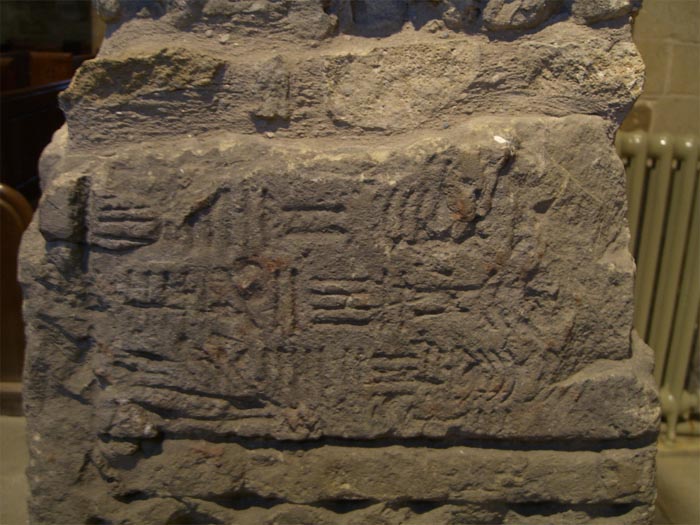

The Hackness Stone

Photo: University og Leeds

The Anglo-Saxon stone at Hackness, North Yorkshire is a special monument, as it has inscriptions both Anglo-Saxon runes, Scandinavian runes and Latin letters and with characters similar the Ogham alphabet.

Today runes not legible, but Stephen reads the runes:

emundr o on æsboa

“Emund owns-me on (at) Asby

Literature:

¤ Hackness stone fra University og Leeds..

¤ www.academia.edu.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Hartlepool Stones

Photo: Stephens.

The Hartlepool stones are so called “pillow-stones,” which was found under the head of the buried. Similar stones are also found in Lindisfarne.

![]()

hilddigyş

This is the woman’s name.

![]()

hildişryş

This is the woman’s name.

Liiteratur:

¤ Runes: An Introduction, Ralph Warren Victor Elliott.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

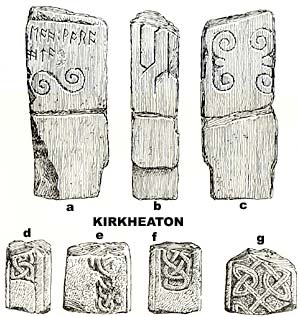

The Kirkheaton Stone

Photo: www.huddersfield1.co.uk

Eoh worohhtae

Eoh wrought (this)

or

Eoh woro htæ

Eoh made (me)

Literature:

¤ www.archaeology.wyjs.org.uk.

¤ www.huddersfield1.co.uk.

¤ Seville Corpus of Northern English.

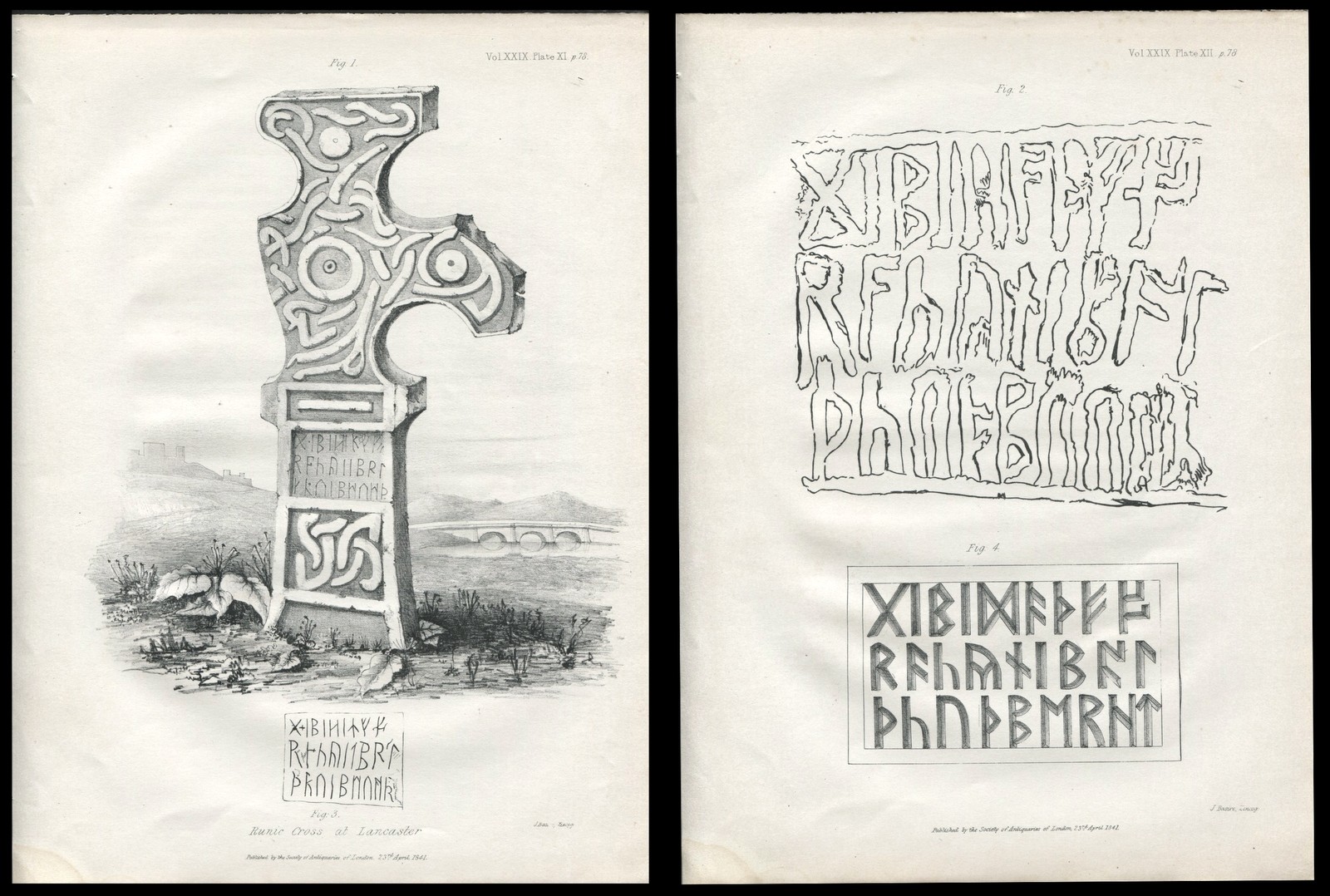

The Lancaster Cross

Photo: The Society of Antiquaries in London, 1841.

The inscription reads:

gibidæş foræ cynibalş cuşbere[ht]

Pray for Cynibalth, Cuthbert

Literature:

¤ Wikipedia – Lancaster_Priory.

¤ Foto: British Museum.

¤ Further Notes on the Runic Cross at Lancaster, John Mitch Kemble.

The Leeds Stone

Photo: Stephens

cune anlaf

King Olaf

This can be Anlaf or Olaf, the son of a Danish king who together with his brothers, Sitric and Ivar came to Ireland 853, and invaded Britania in 866-867, and presumably died there.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

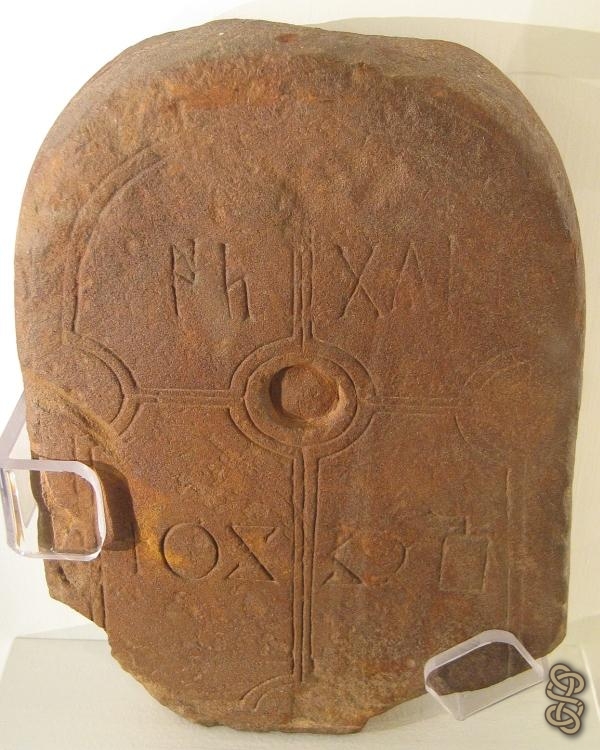

The Lindisfarne Stone I

Photo: Ogneslav ©

This tombstone is dated to about the year 700, and is one of many Anglo-Saxon carved stones found at Lindisfarne. The stone bears the name of a woman, Osgyth.

Literature:

¤ heritage-explorer.co.uk.

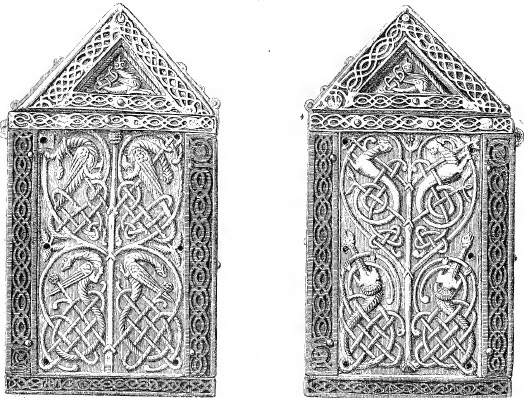

The Mortain Casket – Mortainkisten

The Mortain coffin is shaped like a house and measures 13.5 x 11.5 x 5 cm, and was found in the treasures of church of Saint Evroult, Mortain, in Normandy in 1864. The coffin it dated to the second half of the eighth or the first half of the ninth century. The coffin is made of wood, but is plated with bronze. The coffin is characterized by Christian motives.

A runic text in three lines of old English is written on the back of the lid:

+goodh | e | lpe:æadan

Şiiosneciis | m | eelgewar

ahtæ

Good helpe: Æadan şiiosne ciismel gewarahtæ.

“God help Æadan who made this cismel”.

There are also inscriptions in Latin letters on the coffin.

Literature:

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England, no. 137, pp. 175-176.

¤ Runes: An Introduction Av Ralph Warren Victor Elliott.

The Brunswick Casket

The coffin is made of ivory and measures 12.6 x 12.6 x 6.8cm. It is also known as Gandersheim coffin from the monastery in Saxony, where it was found. It is now kept in Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig.

The coffin was perhaps brought to the continent by an Anglo-Saxon pilgrim before the Vikings attacked Ely in the year 870.

The inscription reads:

uritneşiisixhiræliinmc*hælixæliea*

Şiis and liin kan be read “this” and “lin”, but the rest is not so easy to interpret.

Literature:

¤ Brunswick Runic Caske.

¤ Beckwith, John, Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England, 700-1200, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1974.

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England.

¤ Beckwith, John, Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England, 700-1200

¤ The Runic Inscription on the Gandersheim

The Sandwich Stone

The stone is now in the Royal Museum at Canterbury.

![]()

The inscription reads:

ræhæbul

This is most probably a name.

Literature:

¤ The Sandwich runestone, R.W.V. Elliott.

¤ I.R.Page. Early runic Inscriptions In England.

The Selsey Gold Fragments

Photo: Wikipedia

These two small gold strips (1.8 x 0.5 cm)) appears to be part of the same object, possibly a ring. They were found on a beach near Selsey, West Sussex, and they are now in the British Museum. The inscription is dated to between the late 6th to 8th century.

The inscription read:

![]()

brnrn

anmæ or anmu or anml

There is no good interpretation of the runic text.

Literature:

¤ Bruce Eugene Nilsson, 1973.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

¤ Hines, John, ‘The runic inscriptions of early Anglo-Saxon England’ in Britain 400-600: Language and History, Alfred Bammesberger and Alfred Wollmann

The Southampton Bone Plaque I

Photo: R.I. Page

These two bone fragments are dated to the 9th century, both decorated with a pattern and they have some runes inscribed on edge of the plate. Unfortunately the edge is damaged, so that only the first d-rune can be seen in its entirety. The other runes can be pdln, but no interpretation can be given.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 160.

The Southampton Bone II

Innskriften kan ikke dateres presist, men benet innskriften er riiset på, er fundet i søppelgrop i den tidlige bosetningen i Southampton, Hamwih. I følge I.R. Page, kan innskriften dateres til mellom midt i 7. århundre og 11. århundre. The inscription can not be dated precisely, but the bone the inscription is written on, is found in the garbage pit in the early settlement Southampton, Hamwih. According I.R. Page, the inscription is dated to between the middle of the 7th century and 11th century.

The four runes on the leg reads:

catæ

The word may be related to Old English cat(t) or catte, ie “cat” or “she-cat”.

Alternatively, the inscription can be read katæ,who will be Old-Frisian and will mean “knuckle-bones“

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 168-169.

¤ Campbell, James (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons, pp. 102-103.

The Whithorn Stone

Photo: megalithic.co.uk

The inscription is probably dated to the 9th century or 10th century and reads:

“Pray for Hwitu”.

Hwitu is a woman’s name meaning “white house”.

Literature:

¤ www.megalithic.co.uk.

¤ www.scotsman.com.

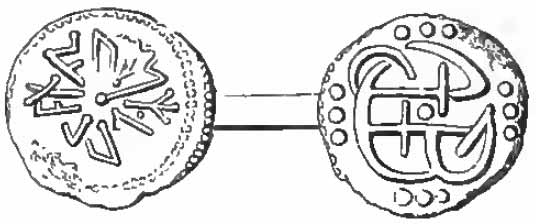

IK 388 – Welbeck Hill Bracteate

The silver Bracteate from Welbeck Hill, located in Irby, Lincolnshire, England is in private ownership. It is found in a woman’s grave and is dated to the 6th century. (Hines 1990:445).

Photo: Stephens

The runes are leftward and reads: law

law may be a mistranslation of the known protective word laþu.

Literature:

¤ Bracteates with runes.

¤ Hines 1990.

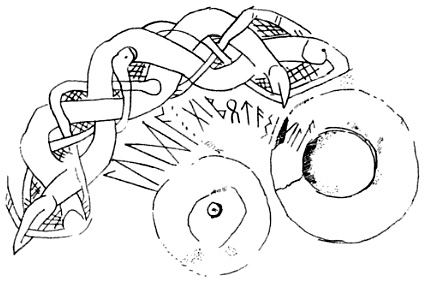

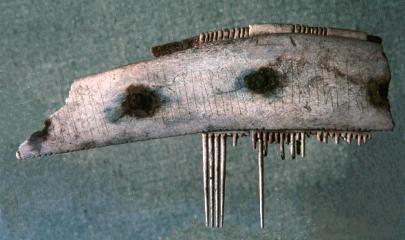

The Whitby Comb

Photo: British museum

The comb was found among rubbish near the ruins of Whitby Abbey. The Runic text begins with the formula dæus mæus. The text continues with a prayer to God to help person, who may be the creator or owner of the comb.

The runes reads:

dæusmæus | godaluwalu | dohelipæcy

Page says that Aluwaludo means eallwealda, i.e. “Almighty”.

“My God: may God Almighty help Cy …”’

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, pp. 164-165.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

¤ Tegning av Witby kammen.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Whitby Spindle Whorl

Photo: Ogneslav ©

The spinning wheel was found during excavations at Whitby Abbey, and is now preserved in the British Museum.

The inscription contains three runes, but only the middle rune, an e-rune, can be read by sure:

leu or ler or uer

All suggestions may be a name.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 170.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Willoghby-On-The-Wolds Bowl

The Bronze bowl is possibly imported from Rhineland and is dated to the 5th – 7th century.

The inscription consists of a rune:

æ

There is a possibility that the rune should be interpreted as an ideograph.

The Æsc-rune may then be owner or creator’s signature or name. Possibly an import from the Rhineland.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, side 91

The Keswick Disc

Photo: R.I. Page

This plate of a copper alloy is 2.9 cm in diameter, and is found in river Yare at Keswick.

We do not know what it is used for, but the text can be followed Page be read:

+ (? or g, n) tlim*(=?s)um(? r d)

There is no reasonable interpretation of the runic text.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 161.

¤ Nytt om runer, nr. 12, side 13.

The Brandon Tweezers Fragment

This fragment of silver is part of a tweezers, dated to the 8th century. Tweezer has a runeinnskkrift which reads:

+ aldred

The inscription is a man’s name.

Literature:

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England, no. 66 o, p. 85.

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 34.

The Brandon Bone Handle

The handle which appears to be made to a tool, is made of bone.

The inscription reads:

wohswildumde[.]ran

wohs wildum deoran or wohs wildum deor en

“(I) grew on a wild beast”.

The text refers to the bone-share the handle is made of.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, pp. 169-170.

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England, no. 65, p. 81.

The Heacham Tweezers

The Heacham tweezer is of metal and dated to the 6th or 7th century, and is held at The Castle Museum in Norwich. Unfortunately, the metal heavily corroded and runes are not well preserved. It appears that it is the same text that is repeated twice.

Of the runes that can be read is a d-, f– and u-rune.

There is no interpretation of the inscription.

Literature:

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

The London Bone

Photo: Nytt om Runer

The bone piece were found in 1996 during excavations at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London. There is a hollow leg, which may have been devoted as a handle for a tool. It is dated to the middle of the 8th century. The Rune text contains some vertical lines that can be only one kind of hyphenation.

The inscription reads:

oeoewşrd or oeoewwrd or oeoeşşrd or oeoeşwrd

The Runic text makes no sense in any of the proposals for reading.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, pp. 169-170.

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

¤ Page, R. I., ‘Runes at the Royal Opera House, London’, Nytt om Runer 12 (1997), p. 13.

The Wardley Copper-Alloy Plate

This metal plate was found with the help of metal detectors and is dated to the 8th century.

The copper plate has implications inscription:

olburg

The inscription may be a part of or a woman name Ceolburg.

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 30.

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

The Blythburgh Bone Writing Tablet

This rectangular-legged breed (9.4 x 6.3 cm) was found before 1902 and are now in the British Museum, is dated to the 8th century. The back of the board has a recess filled with wax, which is written a rune.

The inscription reads:

unş | ocuat**ş | lsunt | mamæmæm

In the sequencelsunt it looks like the author is trying to write a Latin verb with runes, while the sequence mamæmæm, it looks like the person practicing writing runes m and æ .

Literature:

¤ Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse (ed.), The Making of England, no. 65, p. 81.

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

The Mote Of Mark Bone

This small bone fragment (3.3 cm) has a runic inscription, which presumably is dated 650-750 years.

The inscription reads:

aşili

This can be a name in diminutive.

Diminutive is a derived word that denotes a smaller form of what the original word signifies. Diminutive form often with a suffix that is specific to that language. On Norwegian’s diminutivsuffikset -ling for example badgers and manikin, but it is no longer used actively to form new words.

Literature:

¤ Anglosaxon indskrifter.

¤ Laing, L., ‘The Mote of Mark and the origins of Celtic interlace’, Antiquity 49 (1975), p. 101.

¤ wikipedia om Diminutiv.

The Spong Hill Rune Stample

Photo: R.I. Page

During excavation of a graveyard in Spong Hill, Norfolk, it found several urns with runes. It concerns inscriptions with alu-formula and three urns with so-called inverted runes, ltw, all inscriptions dated to the 5th century. (see Hines 1990: 434). Common to all mentioned inscriptions is that they are made with the help of a stamp. Thus we have a masseprduksjon of urns to do. The urns can be seen in The Castle Museum, Norwich.

The runic inscriptions were probably cherish the dead.

Literature:

¤ www.cornucopia.org.uk.

¤ www.englisc-gateway.com.

¤ 11.Howard_Ruth.pdf.

The Long Buckby Silver Strap-End Fragment

Photo: www.finds.org.uk

The silver gilt fragment is broken at both ends and have a distinct h-rune inscribed. The length is 32 mm, and is dated to the second half of the 8th century.

Literature:

¤ finds.org.uk.

The Leek Stone

Photo: Medieval Archaeology.

The stone stands beside the church, and is composed of three parts. The runes are damaged and are not easy to read.

The readable runes reads:

isa and þ bibæ

It gives me no sense.

Literature:

¤ A runic fragment at Leek.

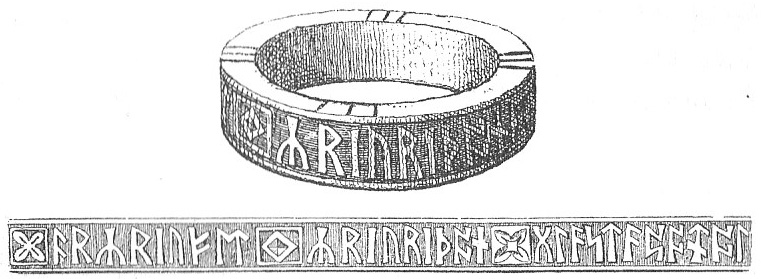

The Cramond Ring

Photo: Stephens

The Cramond ring is in the National Museums Skottland and is dated to between AD 800 and AD 1000.

The inscription reads:

[.]ewor[.]el[.]u

There are differing opinions on the interpretation. National Museums Skottland interprets it “made“. I.R. Page rather inter alia that there may be a name.

Literature:

¤ Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 157.

¤ National Museums Skottland.

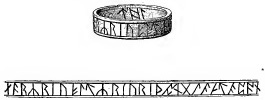

The Bramham Moor Ring

Photo: Stephens

The Bramham Moor ring is 29mm in diameter and is made of gold. The ring is dated to the 9th century. The ring is kept in the National museum in Denmark (no. 8545). The runic text is a magic formula, and is in the same group as the Linstock castle ring, the Kingmoor ring, the copper ring from Northern England and Bramham Moor ring.

The inscription reads: ærkriuflt | kriurişon | glæstæpon?tol

The text is interpreted as a magic formula, with a possible link to two Old English formulas against bleeding.

Literature:

¤ Wikimedia – Bramham Moor Ring.

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, Second Edition, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1999, p. 112.

¤ Paul Johnson, Runics Inscription in Great Britain, 2001, ISBN 1-904263-40-2.

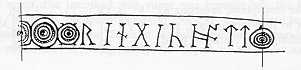

The Copper Ring From North of England

Photo: Stephens

The ring was found in 1869 and is now at Britsh Museum. Rune text is a magic formula, and is in the same group as rings from Linstock castle, Kingmoor and Bramham Moor and Linstock castle.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

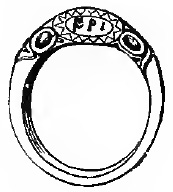

The Kingmoor ring – The Greymoor Hill ring

Photo: Ogneslav ©

This ring was found in Kingmoor in 1817. There is a large gold ring with runes, which is dated the ninth century, now in Britsh Mueum. The runic text is a magic formula, and is in the same group as including rings from Linstock castle and Bramham Moor

The inscription reads:

+ ærkriufltkriurişonglæstæpon

The runic text is a magic formula.

Literature:

¤www.britishmuseum.org.

¤ Paul Johnson, Runics Inscription in Great Britain, 2001, ISBN 1-904263-40-2.

¤ Bilde fra British Museum.

¤ Bilde fra British Museum.

¤ Bilde fra British Museum.

¤ Bilde fra British Museum.

¤ Page, R.I., An Introduction to English Runes, pp. 112-113.

The Linstock castle Ring

The ring with runes is probably from the 9th century, and is made of agate. The ring are kept in the British Museum (catalog no. 186).

The inscription reads:

ery.ri.uf.dol.yri. şol.wles.te.pote.nol

I.R. Page (1999) believes that the runic text is an attempt to write a magic formula, inspired by the school which has been the source of Kingmoor and Bramham Moor rings but that the creator of Linstock Castle ring, has not been versed in the subject. This is also known among bracteates.

Literature:

¤ Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 112.

¤ wikipedia.

¤ www.digital.library.leeds.ac.uk.

The Agate Ring Of West Of England

Photo: Stephens

The Agate Ring ring from the west of England is made of agate, but is now stored at the Britsh Museum. The runic text is a magic formula, and is in the same group as the Linstock castle, the Kingmoor ring and the Bramham Moor ring.

Literature:

¤ Paul Johnson, Runics Inscription in Great Britain, 2001, ISBN 1-904263-40-2.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ R.I.Page, An Introduction to English Runes,, 1973 ISBN 978-0-85115-946-1.

The Wheatley Hill Ring

Photo: Nytt om Runer

The ring is made of silver, measures 19 mm in diameter, and is dated to the 8th century.

The inscription reads:

[h]ringichatt[.]

“I am called a ring”

Literature:

¤ Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 169.

¤ www.ansax.com.

¤ Jessup, Ronald, Anglo-Saxon Jewellery, p. 169.

The Lancashire Ring

Photo: R.I. Page

The text is written with a mix of runes and Latin letters. Okasha, Jessup and Wilson dating the ring to 9th century, while Page prefer to keep it open until somewhere between before 800 to 1100 AD.

The inscription reads:

+ æDREDMECAHEAnREDMECagROf |.

“Ædred owns me, Eanred engraved me

Literature:

¤ Page, R. I., ‘The Inscriptions’ in Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700-1100 in the British Museum, p. 77.

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 115 and pp. 219-220.

The St. Andrews Ring<

Foto: Stephens

This bronze ring is from Fife in Skottland and is dating the years 500-600.

The inscription reads:

isah

If one reads the inscription facing right as Isah, or left facing as Hasi, both reading methods, will give a man’s name.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Ring From Unknown Location In England

Foto: Stephens

The ring is dated to the year 800-900 and has a runic inscription.

The inscription reads:

owi

The Runic text is a man’s name.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Coquet Island Ring

Photo: Stephens

The ring is made of silver and dated to the year 800-900.

The inscription reads:

þis is siuilfur

Englesk: “This is silver”.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Selsey Ring

The ring is made of gold, is preserved in two parts at the British Museum and dated to the year 700-800.

![]()

I.R. Page suggests that the inscription read:

bruþr niclas on el

“Brother Niclas on (of) El…”.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Thames Exchange Ring

Photo: Ogneslav ©

Finger ring made of brass is dated to the 900s. It is kept at the Museum of London.

The inscription read:

t futhniine

The first rune may be either a t-rune or ae-rune.

futh may represent the first letters of the runic alphabet, while ine at the end might be a man named “Ine”.

However, also “fuş” means fuğ which is the term for the female pussy . The word in this sense is coated in many Nordic inscriptions from the Middle Ages, where scontext not give a doubt about what is being written. The inscriptions like this is not always understandable. Christians Londoners preserved some of the beliefs of their pagan ancestors, and used runes to write magic and spells.

Literature:

¤ archive.museumoflondon.org.uk.

¤ Nyt om runer

The Northumbria Bronch

Photo: Stephens

We do not know much about this locket because it is lost. It was last seen by Mr. Kemble in 1847, but we assume that it is from the year 600-700.

gudrd mec wroh(t)e. ælchfrith mec a(h)

Gudrid me wrougth. Ælchfrith oweth (owns)

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Falstone Stone

Photo: Stephens

The inscription read:

eomær þoe seotteo

æftær roetberhtæ

begun æftær eomæ

gebidæd der saule

Eomær this set, after Hroetberth this beacon (mark, memoiral), after his eme (uncle). Bede (bid, pray-ye) the (his) soul

The same text is also written with Latin bogstaver. The stone can be from 700 AD.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Lindisfarne Coffin – The Saint Cuthbert’s Coffin

Photo: Stephens

The Lindisfarne coffin is made of wood and has several short Lantin inscriptions, and one small inscription in runes. It is dated to the year 698. The runic inscription seems to be secondary, as it is in Latin and there are indications that it was copied from a manuscript.

The rune inscription is very damaged, but the following are legible:

ihs xps mat(t)[h](eus)

The inscription is interpreted “Jesus Matheus”

Literature:

¤ Wikipedia.

¤ Page, R. I., ‘Roman and runic on St. Cuthbert’s coffin’, s. 317 og s. 323-324.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

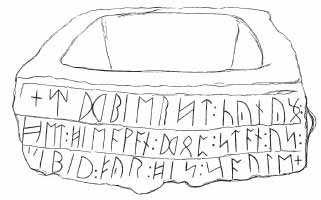

The Bingley Baptismal Font

Photo: Stephens

The Bingley Baptismal font is decorated with borders, and is dated to the year 768-770.

The inscription read:

eadbierth cunung

het hieawan doep-stan us

(G)ibid fur his saule

Eadbierth King. Hote (ordered, bade) to – hew this – Dip-Stone (font) for- us. Bid (pray-thou) for his soul.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

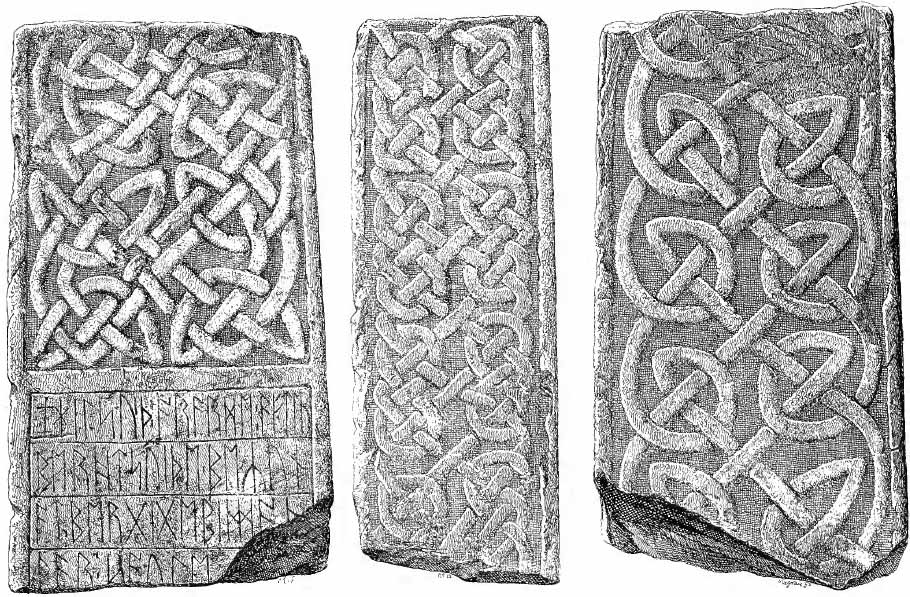

The Thornhill Stone I

Photo: Stephens

The stone is from Thornhill in Yorkshire and is dated to the year 700-800.

The inscription read:

eşelberth settæ

æfter eþelwini deringæ

Ethelberth set-up-this after Ethelwini Dering

Literature:

¤ www.huddersfield1.co.uk.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Thornhill Stone II

Photo: Stephens

The stone is from Thornhill in Yorkshire and is dated to the year 700-800.

The inscription read:

eadred sete afte eateyonne

Eadred set up this after the lady Eateya

Literature:

¤ www.huddersfield1.co.uk.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Thornhill Stone III

Photo: Stephens

The stone is from Thornhill in Yorkshire and is dated to the year 700-800.

The inscription consists of 4 lines in spelling rhyme:

igilsuiþ arærde

after berhtsuiþe

becun at bergi

gebiddaþ þær saule

Igilsuith a-reared (raised) after (in minne of) this beacon (pillar-staone) at (on, close to) the barrow (how, tumulus). Bid (pray-ay) for the soul.

Literature:

¤ www.huddersfield1.co.uk.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

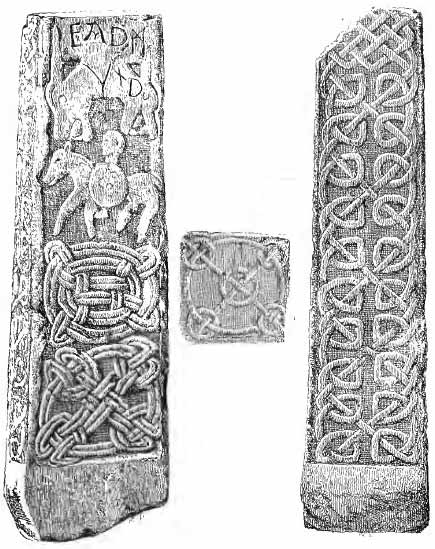

The Chester-Le-Street Stone

Photo: Stephens

Chester-Le-Streetstenenfrom N. Durham and is dated to the year 700-800. In this inscription there are 7 characters, but only two runes, the rest are Latin letters.

The inscription read:

EADmUnD

Eadmund is a man’s name.

Literature:

¤ www.huddersfield1.co.uk.

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Irton Stone

Photo: Stephens

The Irton stone from Cumberland and is dated to the year 700-800.

The inscription read:

gibidæþ

foræ….

Bid-ey (pray) for…

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

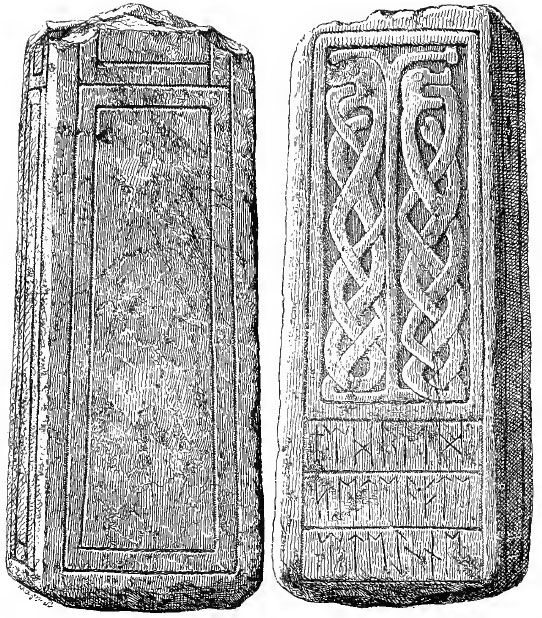

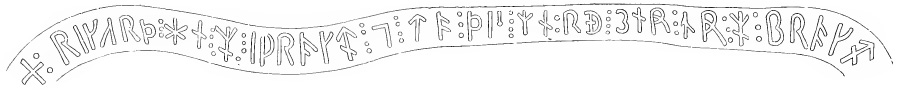

The Bridekirk Baptismal Font

Photo: Stephens

The baptism font is from Cumberland and is dated to the year 1100 to 1200. The runes are a mix of old-skandianavian and Old-English runes, and the language is a mixture of early Northern English and early Norse. The inscription is written in rhyme.

The inscription read:

rikarth he me iwrokte

and to this merthe ?erner me brokte

Richard he me I-wrougth (made), and to his mirth (beauty) yern (glad) me brougth

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Bilde av døpefonten.

The Alnmouth Stone

Photo: Stephens

The Alnmouth stone is from Northumberland and is dated to the year 913.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

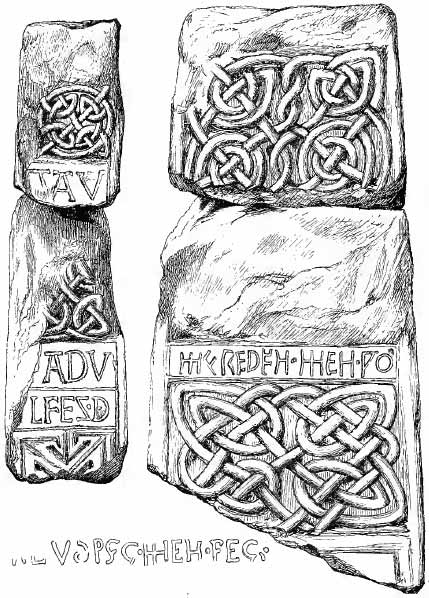

The Monk Wearmouth Stone

Photo: Stephens

The Monk Wearmouth stone is from Durham and is dated to the year 822.

The inscription read:

tidfirþ

Tidfirth or Tidferth was the last bishop of Hexham.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Kirkdale Stone

The stone is from Yorkshire and heavily damaged. The only rune that is legible is:

![]()

Thats a ng-rune. Dated to the year 800-900.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Bakewell Stone

Photo: Stephens

The Bakewell stone is from Derbyshire and is dated to the year 600-700.

The inscription read:

(m)ingh(o)

helg

The first line can be part of a name or a place names. The second line can be a fragment of the word “holy”.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

The Cleobury Mortimer Sun Dial

![]()

Photo: Stephens

The Cleobury Mortimer solar disk is from Shropshire and is dated to the year 500-600.

The inscription read:

claæo iwi

Let the clow (pointer) eye (show you)!

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Bilde av gjenstanden.

The Boarley Disc-Brooch.

The Boarley cobber broosh is found in Kent. The broosh is dated to the last part of the 6. or the first part of the 7. century.

The inscription read:

![]()

atsil or ætsil

Presumably not the rune carver has not completed the intended text.

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The West Heslerton Cruciform Brooch

Copper brooch is from Yorkshire and it is cruciform. It is dated to the first part of the 6th century.

The inscription read:

![]()

One can read the runic text either neim, if it is read from right to left, or mien, if one reads the runic text from left to right.

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

Chessel Down I – Chessel Down Bronze Pail,

The Bronze pail that was found in woman’s grave on the Isle of Wight and is dated to the year 520-570 (Hines 1990: 438). The team is importing goods from the eastern Mediterranean and the runes were carved over the original decoration, and thus it is not anticipated that the runes are carved when the team was created.

The inscription read:

???bwseeekkkaaa

The inscription is similar Secretes Runes, eg sequence şmkiiissstttiiilll from Gørlev. See more about Secretes Runes.

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

Chessel Down II

The object is made of silver and was found in a rich man’s tomb on the Isle of Wight.

The inscription read:

æko:?ori

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

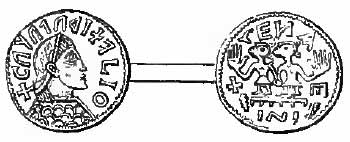

Suffolk Gold Coins

Three gold coins Skilling, one from St. Albans and two from Coddenham in Suffolk is dated to about the year 660, is probably turned with the same stroke shape.

The inscription read:

![]()

desaiona

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

Kent II – Silver Coins from Kent

The coins from Kent belong to the so-called “pada“-coins and presumably turned approximately 660-670 years.

The inscription read:

![]()

pada

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

Kent III, IV Silver Coins

Silver coins from Kent is dated to the end of the 7th century.

The inscription read:

![]()

æpa og epa

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Upper Thames Valley Gold coins

Four gold coins were funded in Upper Thames Valley which is dated to the year 620.

The inscription read:

![]()

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Cleatham bowl

Cleatham copper bowl was funded in woman’s grave in South Humberside Shire and is dated to the 6th to 7th century.

The inscription read:

![]()

??edih eller hide??

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Watchfield Copper-Alloy Fittings

Watch Field copper fittings was found in a man’s grave on the border between Mercia and Wessex, is dated to the years 520-570.

The inscription read:

![]()

hæriboki:wusæ

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Wakerley Brooch

Wakerley brooch is from Northamptonshire and is made of a copper alloy. The broosh is dated to the year 525-560.

The inscription read:

![]()

Buhui

Literature:

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England.

The Chessell Down Sword

Photo: Stephen

Chessell Down sword is found on the Isle Of Wight and is dated to the year 500-600.

The inscription read:

æco soeri

? Awe (terror, death and destruction) to the sere (brynie, armor, weapons, of the foe)! ?

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

¤ Bilde av sverdet.

The Coin from Wyk, Utrecht

Photo: Stephen

The Silver Coin monogrammed can stand for King Ecgberht, king of Wessex, who died in the year 836.

The inscription read:

lul on áuasa / áusa

Lul on (of) Áuasa or Lul of Áusa (struck this piece)

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

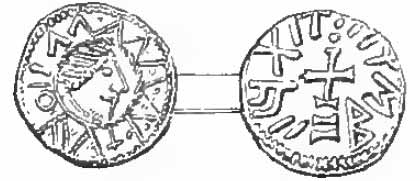

Bracteate, Stephens no 74, England

Photo: Stephen

The inscription read:

scanomodu

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884.

Bracteate, Stephens no 75, England

Photo: Stephen

The inscription read:

æniwulu ku

Æniwulu (Anwulf) King

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884

Bracteate, Stephen no. 77, Eastleach Turville, Gloucestershire, England

Photo: Stephen

The inscription read:

bea(r)tigo)

Thats a man’s name.

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884

The Urswick Cross

There is no certain interpretation of the inscription.

Literature:

¤ www.megalithic.co.uk.

¤ monumentsnetwork.org.

¤ monumentsnetwork.org.

The Collingham Stone

Photo: Stephen

The Collingham stone is from Yorkshire and is dated to the year 651. Today it looks just as one stone, but is in reality two stones.

The inscription read:

æfter onswini cuning)

After Onswini, King

Literature:

¤ The Collingham Runic Inscription.

The Dearham Stone

Photo: Stephen

The Dirham stone is from Dirham in Cumberland and is dated to the year 850-950. The stone is damaged and a large part of the inscription is lost, but it is sure what once stood written.

The inscription read:

(krist s)u(l) gi-niæra

May Christ his soul nære (bless, save)!

Literature:

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884

The Llysfaen Ring

The ring is made of gold and niello and is dated to the 9th century. It is in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The inscription consists both of Latin letters and a rune:

+ A | LH | ST | An

The text is interpreted as a old English name.

Litteratur:

¤ Okasha, A Hand-List of Anglo-Saxon Non-Runic Inscriptions, no 86, pp. 98-99.

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England

The Wardley Copper-Alloy Plate

The Metal plate was found using metal detectors and it is dated to the 8th century.

The inscription reads:

… olburg

This can be a part of a female name Ceolburg.

Litteratur:

¤ Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes, p. 30.

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England

The Heacham tweezers

The Tweezers is dated to the 6th or 7th century and is now preserved in the Castle Museum in Norwich. The metal is heavily corroded, so the two halves of the preserved texts, is not readable, but it seems to be the same text that is repeated two times.

The only runes which can be read is a d-rune, f-rune og en u-rune.

Litteratur:

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England

Litteratur:

¤ R.I. Page, On the Transliteration of English Runes

¤ Bruce Dickens, Runic and heroic poems of the old Teutonic peoples, 1915.

¤ Bracteates With Runes

¤ Frisian Runic History.

¤ Runic inscriptions in or from the Netherlands.

¤ The runic and other monumental remains of the isle of Man.

¤ Early Runic Inscriptions in England

¤ Anthea Fraser Gupta, The Hackness Cross

¤ A Runic Inscription from Baconsthorpe, Norfolk

¤ George Stephens, On an Ancient Runic Casket Now Preserved in the Ducal Museum, Brunswick

¤ Georg Stephens, Handbook of The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 1884

¤ A Runic Rragment at Leek

¤ R.I. Page, On the Transliteration of English Runes

¤ The Collingham Runic Inscription

¤ The Dover Brooch

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England I

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England II

¤ Inscription and communication in Anglo Saxon England III

¤ Frisian runes revisited – T.Looijenga

¤ The Runic Script and its Characters in Old English and Middle English Texts

¤ Valdemar Bennike, Nord-Friserne og deres land. Skildringer fra Vesterhavs-øerne

¤ Ekstern link: The Corpus Of Frisian Runic Inscriptions

¤ Ekstern link: www.esswe.org.

¤ Ekstern link: www.englishfolkchurch.com.

¤ Ekstern link: wikipedia, Runediktene.

¤ Ekstern link: www.ufdc.ufl.edu.

¤ Ekstern link: en.wikipedia.org

¤ Ekstern link: en.wikipedia.org